Unit4 - Introduction to Program Maintenance

Program maintenance refers to the process of making changes to a software system after it has been deployed. This phase is a critical aspect of the software development life cycle and is essential for ensuring that the software remains effective, efficient, and adaptable to evolving requirements. Program maintenance encompasses various activities, including fixing bugs, updating features, enhancing performance, and addressing compatibility issues. Program maintenance is an ongoing process that ensures software remains valuable and adaptable throughout its lifecycle. It requires a systematic approach, collaboration among development teams, and the use of effective tools and methodologies to manage changes successfully. Here's an introduction to the key aspects of program maintenance:

-

Types of Maintenance:

- Corrective Maintenance: Involves fixing defects or bugs discovered during the usage of the software. The goal is to restore the system to its proper functioning.

- Adaptive Maintenance: Focuses on adapting the software to changes in the environment, such as new hardware or operating system versions.

- Perfective Maintenance: Aims to improve the software by adding new features, enhancing existing ones, or optimizing performance.

- Preventive Maintenance: Involves activities aimed at preventing future issues, such as restructuring code for better maintainability.

- Emergency Maintenance: Involves fixing critical issues that affect the functioning of the software.

-

Reasons for Maintenance:

- Changing Requirements: As business needs evolve, software must be updated to meet new or modified requirements.

- Bug Fixes: Identifying and rectifying defects to ensure the software functions correctly.

- Performance Improvement: Optimizing code for better speed, efficiency, or resource utilization.

- Technology Upgrades: Adapting the software to work with new technologies, libraries, or platforms.

-

Challenges in Program Maintenance:

- Understanding Legacy Code: Dealing with code that may have been written by different developers, with varying coding styles and documentation.

- Regression Testing: Ensuring that changes made during maintenance do not introduce new bugs or break existing functionality.

- Resource Constraints: Limited time, budget, and expertise can pose challenges during maintenance activities.

-

Documentation:

- Code Documentation: Clear and comprehensive documentation is crucial for understanding the existing codebase and facilitating future maintenance.

- Change Logs: Keeping track of modifications made during maintenance for accountability and future reference.

-

Tools and Techniques:

- Version Control Systems: Using tools like Git to manage different versions of the code, making it easier to track changes and collaborate.

- Automated Testing: Implementing test suites to quickly identify and rectify issues without manual intervention.

- Refactoring: Restructuring the code without changing its external behavior to improve readability, maintainability, and performance.

-

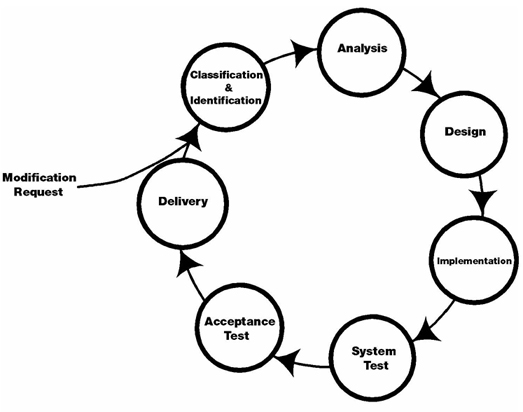

Life Cycle of Maintenance:

- Identification of Issues: Detecting problems through user feedback, monitoring, or automated testing.

- Analysis: Understanding the nature and scope of the issue.

- Fixing: Implementing the necessary changes or improvements.

- Testing: Verifying that the changes are successful and do not introduce new problems.

- Deployment: Introducing the modified software into the production environment.

Why Program Maintenance?

Program maintenance is crucial for several reasons, and its importance becomes evident throughout the lifecycle of software. Here are some key reasons why program maintenance is essential:

-

Adaptation to Changing Requirements:

- Business needs and user requirements are subject to change over time. Program maintenance allows software to be modified and extended to accommodate these changes, ensuring that the application remains relevant and useful.

-

Bug Fixing and Issue Resolution:

- No software is free of bugs or defects. Maintenance is necessary to identify, analyze, and rectify these issues to ensure the software functions as intended. Regular bug fixing contributes to the reliability and stability of the system.

-

Enhancing Performance:

- Over time, software may experience performance bottlenecks or inefficiencies. Maintenance activities, such as performance tuning and optimization, aim to improve the speed, responsiveness, and resource utilization of the software.

-

Security Updates:

- With the ever-evolving landscape of cybersecurity threats, software maintenance is crucial for addressing security vulnerabilities. Regular updates and patches help protect the system from potential security breaches and unauthorized access.

-

Compatibility with New Technologies:

- Hardware, operating systems, and third-party libraries evolve over time. Program maintenance ensures that software remains compatible with the latest technologies and platforms, preventing obsolescence and improving interoperability.

-

User Feedback and Feature Requests:

- User feedback provides valuable insights into the usability and functionality of software. Maintenance allows developers to incorporate user suggestions, address usability issues, and add new features to meet evolving user expectations.

-

Cost-Effectiveness:

- Continuous maintenance can be more cost-effective than developing an entirely new system. Regular updates and improvements help prevent the accumulation of technical debt, making it easier to manage and extend the existing codebase.

-

Longevity of the Software:

- Well-maintained software can have a longer lifespan. Instead of discarding and rebuilding, maintenance enables the software to evolve and adapt, extending its usefulness and providing a higher return on investment.

-

Regulatory Compliance:

- Regulatory requirements and industry standards may change over time. Program maintenance ensures that software remains in compliance with these standards, reducing legal and compliance risks.

-

Knowledge Transfer and Succession:

- As team members come and go, maintaining clear and comprehensive documentation along with a well-organized codebase facilitates knowledge transfer. This is crucial for ensuring that new developers can understand and contribute to the existing software.

Types of Maintenance

Program maintenance can be broadly classified into five categories:

-

Corrective Maintenance:

- Corrective maintenance involves fixing defects or bugs discovered during the usage of the software. The goal is to restore the system to its proper functioning. Corrective maintenance is often the most common type of maintenance and is typically performed as soon as a bug is detected. It is also known as bug fixing or reactive maintenance.

-

Adaptive Maintenance:

- Adaptive maintenance focuses on adapting the software to changes in the environment, such as new hardware or operating system versions. It is often necessary to ensure that the software remains compatible with the latest technologies and platforms. Adaptive maintenance is typically performed after the release of a new version of the operating system or a third-party library.

-

Perfective Maintenance:

- Perfective maintenance aims to improve the software by adding new features, enhancing existing ones, or optimizing performance. It is often performed to meet evolving user expectations or to improve the usability of the software. Perfective maintenance is typically performed after the release of a new version of the software.

-

Preventive Maintenance:

- Preventive maintenance involves activities aimed at preventing future issues, such as restructuring code for better maintainability. It is often performed to reduce technical debt and improve the quality of the codebase. Preventive maintenance is typically performed during the development phase of the software.

-

Emergency Maintenance:

- Emergency maintenance involves fixing critical issues that affect the functioning of the software. It is often performed to address security vulnerabilities or other high-priority issues. Emergency maintenance is typically performed as soon as the issue is detected.

Major Problem Areas of Program Maintenance

While program maintenance is essential for the longevity and effectiveness of software, it comes with its own set of challenges and problem areas. Addressing these challenges is crucial to ensure that maintenance activities are performed efficiently and effectively. Here are some common problem areas associated with program maintenance:

-

Legacy Code:

- Dealing with legacy code, which may be outdated, poorly documented, and difficult to understand, poses a significant challenge. Understanding and modifying such code can be time-consuming and error-prone.

-

Lack of Documentation:

- Insufficient or outdated documentation hinders the maintenance process. Clear and up-to-date documentation is essential for new developers joining the project and for understanding the existing codebase.

-

Dependency Management:

- Managing dependencies on external libraries, frameworks, and components can be challenging. Compatibility issues and changes in third-party software may necessitate updates or modifications to maintain the overall system's integrity.

-

Regression Issues:

- Introducing changes during maintenance can lead to unintended consequences, causing new issues or "regressions." Comprehensive regression testing is crucial to ensure that modifications do not negatively impact existing functionality.

-

Resource Constraints:

- Limited resources, including time and budget, can impede effective program maintenance. Balancing the need for maintenance activities with ongoing development efforts and new feature implementation is often a challenge.

-

Scope Creep:

- As maintenance activities progress, there is a risk of scope creep, where additional features or changes are introduced beyond the originally planned scope. This can lead to extended timelines and increased complexity.

-

Resistance to Change:

- Developers or stakeholders may resist making changes to a stable system, fearing potential disruptions or introducing new issues. Overcoming resistance and emphasizing the importance of proactive maintenance can be challenging.

-

Fragmented Knowledge:

- Knowledge about the software may be concentrated within specific individuals or teams. If this knowledge is not shared or documented, the departure of key team members can result in a loss of expertise, hindering maintenance efforts.

-

Inadequate Testing Practices:

- Inadequate testing, including insufficient unit testing, integration testing, or user acceptance testing, can lead to undetected issues. Rigorous testing practices are essential to maintain software reliability.

-

Decision-Making Challenges:

- Decision-making during maintenance, such as whether to fix a bug, refactor code, or introduce a new feature, can be complex. Balancing short-term gains with long-term maintainability requires careful consideration.

-

Version Control Issues:

- Inconsistent or improper use of version control systems can lead to confusion, conflicts, and difficulties in tracking changes. Ensuring proper version control practices is essential for a smooth maintenance process.

-

Communication Gaps:

- Poor communication between development teams, stakeholders, and users can lead to misunderstandings about requirements, priorities, and the impact of maintenance activities.

Cost Issues in Program Maintenance

Cost issues in program maintenance can arise due to various factors, and managing these costs is a critical aspect of maintaining a software system over time. Here are some common cost-related challenges associated with program maintenance:

-

Budget Constraints:

- Limited financial resources can impact the ability to allocate sufficient funds for program maintenance. Organizations may prioritize new development projects over maintenance, leading to delayed updates and increased technical debt.

-

Resource Allocation:

- Allocating skilled developers and other resources to maintenance tasks can be challenging. The availability of experienced personnel who understand the existing codebase is crucial for efficient maintenance, but competing priorities may result in resource shortages.

-

Time Constraints:

- Time constraints often accompany maintenance activities. Urgent bug fixes or critical updates may need to be implemented quickly, potentially leading to rushed and less thoroughly tested solutions.

-

Scope Creep and Change Requests:

- Expanding the scope of maintenance activities or addressing numerous change requests can lead to increased costs. It's essential to manage scope effectively and prioritize changes based on their impact and importance.

-

Testing Costs:

- Rigorous testing is necessary during maintenance to ensure that changes do not introduce new issues. Testing, especially regression testing, can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, adding to the overall maintenance costs.

-

Training and Knowledge Transfer:

- Bringing new team members up to speed on the existing codebase requires training and knowledge transfer. The associated costs may include time spent by experienced team members to mentor and educate newcomers.

-

License and Tool Costs:

- Using specialized tools or acquiring licenses for updated software components can contribute to maintenance costs. This is particularly relevant when upgrading or adapting the software to work with new technologies.

-

Communication Costs:

- Effective communication is crucial during maintenance activities. If communication between team members, stakeholders, and users is not streamlined, misunderstandings can occur, leading to rework and increased costs.

-

Vendor Dependence:

- Reliance on external vendors for software components or services may expose an organization to increased costs. Changes in vendor pricing, support agreements, or the need for additional services can impact the overall cost of maintenance.

-

Technical Debt Accumulation:

- Neglecting maintenance can lead to the accumulation of technical debt, making it more challenging and costly to address issues in the future. Proactive maintenance can help prevent the escalation of technical debt.

-

Emergency Fixes:

- Unforeseen issues or critical bugs that require immediate attention can result in emergency fixes. These urgent fixes may demand more resources and lead to increased costs due to the need for quick resolution.

-

Inadequate Planning:

- Lack of a well-defined maintenance plan and roadmap can result in ad-hoc and reactive approaches, leading to inefficiencies and increased costs.

Impact of Software Errors

Software errors, commonly known as bugs or defects, can have a wide-ranging impact on both users and organizations. The severity of the impact varies depending on the nature of the error, the context in which the software is used, and the criticality of the affected functionality. Here are some common impacts of software errors:

-

User Frustration:

- Users encountering errors may experience frustration and dissatisfaction with the software. This negative user experience can lead to a decline in user trust and loyalty.

-

Loss of Productivity:

- Software errors can disrupt normal workflows, causing downtime and a loss of productivity for users. In business and organizational settings, this can have financial implications.

-

Data Loss or Corruption:

- Critical errors may result in the loss or corruption of data. This is particularly problematic in applications that handle sensitive or valuable information.

-

Security Vulnerabilities:

- Some software errors can lead to security vulnerabilities, making the system susceptible to unauthorized access, data breaches, or other malicious activities. Security flaws can have severe consequences for both users and organizations.

-

Financial Impact:

- Software errors can have direct financial implications. The cost of fixing bugs, addressing security vulnerabilities, and compensating for losses incurred due to downtime or data breaches can be substantial.

-

Reputation Damage:

- Persistent or high-profile software errors can damage the reputation of the software developer or the organization deploying the software. Users may lose confidence in the reliability and quality of the software.

-

Customer Support Overhead:

- Errors often lead to an increase in customer support requests. Addressing these inquiries and providing assistance to users affected by issues can strain customer support resources.

-

Compliance and Legal Issues:

- In some cases, software errors may result in non-compliance with industry regulations or legal requirements. This can lead to legal challenges, fines, or other regulatory consequences.

-

Delayed Timelines:

- Fixing errors can lead to project delays. If not addressed promptly, errors may accumulate, and the overall timeline for software development and deployment may be extended.

-

User Safety Concerns:

- In safety-critical systems such as medical devices, automotive software, or industrial control systems, software errors can pose risks to user safety. This is a particularly serious consequence that may lead to accidents or injuries.

-

Difficulty in System Integration:

- Software errors can complicate the integration of different software components or third-party services. Interoperability issues can arise, hindering the smooth functioning of the entire system.

-

Operational Inefficiencies:

- Errors may result in operational inefficiencies, impacting the overall performance of the software. This can lead to increased resource consumption, longer response times, and degraded system efficiency.

The problem of Software Modification

Software modification, which includes making changes to existing software, is a common and necessary aspect of the software development life cycle. However, it comes with its own set of challenges and complexities. Here are some key problems associated with software modification:

-

Code Complexity:

- Over time, software code can become complex, making it challenging to understand and modify. Lack of proper documentation and adherence to coding standards can contribute to this complexity.

-

Legacy Code Issues:

- Software modification often involves dealing with legacy code written by different developers with varying styles and practices. Understanding and modifying such code can be time-consuming and error-prone.

-

Dependency Management:

- Software may have dependencies on external libraries, frameworks, or services. Updating or modifying the software may require managing these dependencies, which can be complex and may introduce compatibility issues.

-

Unintended Consequences (Regeneration):

- Making changes to one part of the code may have unintended consequences in other areas. This phenomenon, known as "regeneration," can lead to the introduction of new bugs or issues.

-

Testing Challenges:

- Rigorous testing is essential after making modifications to ensure that the changes do not adversely affect the existing functionality. However, thorough testing can be time-consuming and resource-intensive.

-

Documentation Gaps:

- Inadequate or outdated documentation can impede the modification process. Developers may struggle to understand the existing codebase and the impact of potential changes without comprehensive documentation.

-

Maintaining Compatibility:

- Modifications need to be compatible with existing software versions, user environments, and hardware configurations. Ensuring backward compatibility can be a significant challenge, especially in large and complex systems.

-

Scope Creep:

- Modifications may lead to scope creep, where additional changes or features are introduced beyond the initially planned modifications. Managing and controlling the scope of modifications is essential to avoid project overruns.

-

Resource Constraints:

- Limited resources, including time and budget, can affect the ability to make modifications promptly. Balancing modification activities with ongoing development efforts and addressing competing priorities is a common challenge.

-

Risk of Breaking Existing Functionality:

- Modifying software introduces the risk of breaking existing, working functionality. Ensuring that modifications do not adversely impact the overall system requires careful planning and testing.

-

Knowledge Transfer:

- The need for knowledge transfer becomes crucial when different developers work on the same codebase. Lack of effective knowledge transfer can lead to misunderstandings and errors during the modification process.

-

Vendor Lock-In:

- If the software relies heavily on third-party components or services, modifications may be constrained by the limitations imposed by vendors. This can limit the flexibility to make desired changes.

Time Schedule, User-Need Satisfaction

Achieving user need satisfaction within a specified time schedule is a critical goal in software development. It involves aligning development processes with user expectations, delivering features and improvements on time, and ensuring that the software meets or exceeds user needs. Here are key considerations to balance time schedules and user need satisfaction:

-

User-Centric Approach:

- Begin by understanding and prioritizing user needs. Conduct user interviews, surveys, and usability testing to gather insights. Identify critical features and functionalities that directly contribute to user satisfaction.

-

Define Clear Requirements:

- Clearly define and document user requirements. This includes functional and non-functional requirements, ensuring that both developers and stakeholders have a shared understanding of what needs to be delivered.

-

Agile Development:

- Adopt agile development methodologies, such as Scrum or Kanban, to facilitate iterative and incremental development. Agile allows for flexibility in responding to changing requirements and priorities, promoting better user satisfaction.

-

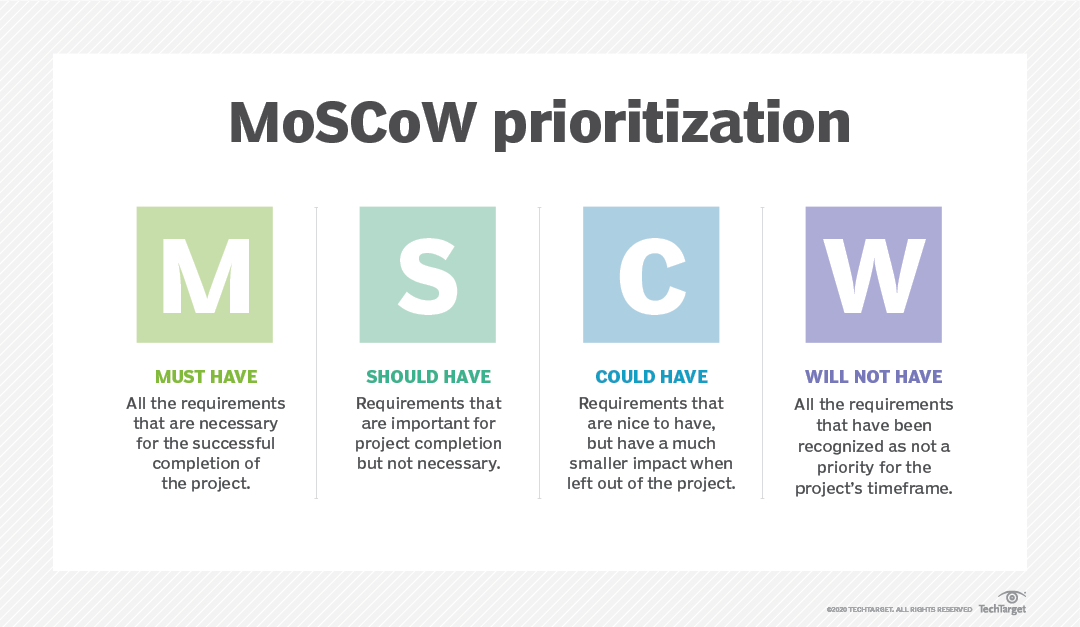

Prioritization:

- Use prioritization techniques (e.g., MoSCoW method) to identify and focus on high-priority features. This ensures that essential functionalities are addressed first, contributing to user satisfaction even if there are time constraints.

-

Time Estimation:

- Implement accurate time estimation techniques for each development phase. This includes breaking down tasks, considering dependencies, and involving the development team in estimating effort. Realistic timeframes prevent overcommitting and help manage user expectations.

-

Prototyping and Feedback:

- Create prototypes or minimum viable products (MVPs) early in the development process. Gather user feedback to refine features and functionalities, ensuring that the final product aligns closely with user expectations.

-

Continuous Communication:

- Maintain open and continuous communication channels between developers, project managers, and end-users. Regularly update stakeholders on progress, and address any concerns or changes in user needs promptly.

-

User Acceptance Testing (UAT):

- Involve users in UAT to ensure that the software meets their expectations before full deployment. UAT allows users to validate that the implemented features align with their needs and that any issues are addressed before the final release.

-

Iterative Improvement:

- Plan for iterative improvements based on user feedback and evolving requirements. Even after the initial release, continuous updates can address additional user needs and enhance overall satisfaction.

-

Automated Testing:

- Implement automated testing to catch bugs and issues early in the development process. This helps maintain a stable and reliable software system, contributing to user satisfaction by minimizing disruptions.

-

User Training and Support:

- Provide adequate training resources and support materials for users. A well-supported user community is more likely to be satisfied with the software, even if certain features take time to be fully implemented.

-

Post-Release Monitoring:

- Monitor the software post-release to identify and address any issues or user needs that may arise after deployment. This ongoing attention to user satisfaction helps build trust and loyalty.

Program Documentation�

Program documentation is a crucial aspect of software development that involves creating and maintaining written materials to describe and explain various aspects of a software system. Well-documented code and supporting documents facilitate understanding, collaboration, maintenance, and future development. Here are key components of program documentation:

-

Code Comments:

- Include comments within the source code to explain the purpose, logic, and functionality of individual code segments. Comments should be clear, concise, and updated as the code evolves.

-

Inline Documentation:

- Use inline documentation to provide detailed explanations of functions, classes, modules, and variables. This documentation is often written in a specific format (e.g., using tools like Doxygen or Javadoc) and can be automatically generated into comprehensive documentation.

-

README Files:

- Include README files in project directories to provide a quick overview of the project. README files typically include information about project structure, dependencies, installation instructions, and basic usage.

-

User Manuals:

- Develop user manuals or guides to help end-users understand how to use the software effectively. This documentation should include step-by-step instructions, FAQs, and troubleshooting information.

-

API Documentation:

- If the software exposes an application programming interface (API), document the API thoroughly. API documentation should cover endpoints, parameters, responses, error handling, and any authentication requirements.

-

Architecture and Design Documents:

- Create high-level architecture and design documents that outline the overall structure of the software, including components, interactions, and dependencies. These documents help developers understand the system's design principles.

-

Database Documentation:

- Document the database schema, including tables, relationships, and data types. This information is valuable for developers, database administrators, and anyone interacting with the database.

-

Version History:

- Maintain a version history document that logs changes made to the software over time. This includes details about bug fixes, feature additions, and improvements for each release.

-

Coding Standards and Guidelines:

- Establish and document coding standards and guidelines that developers should follow. This ensures consistency across the codebase and makes it easier for team members to understand and contribute to the project.

-

Testing Documentation:

- Document testing procedures, including test plans, test cases, and test results. This documentation helps ensure that testing processes are thorough and repeatable.

-

Deployment Documentation:

- Provide documentation for deployment procedures, covering how to install, configure, and deploy the software in different environments. Include information on dependencies, system requirements, and any necessary configurations.

-

License and Legal Information:

- Clearly state the software's license and include any legal disclaimers or notices. This is essential for compliance and informs users about the terms under which they can use, modify, and distribute the software.

-

Maintenance Procedures:

- Document procedures for maintaining and updating the software, including how to address bugs, apply patches, and manage software updates.

-

Dependencies Documentation:

- List and describe external dependencies, libraries, and frameworks used by the software. Include information about versions, licenses, and any specific configurations.

-

Contributor Guidelines:

- If the project is open source or involves contributions from multiple developers, provide contributor guidelines. This documentation should outline how others can contribute, submit bug reports, and propose changes.

Documentation Standard

A documentation standard is a set of guidelines and conventions that dictate how documentation should be created, organized, and maintained within a software development project. Establishing a documentation standard is crucial for promoting consistency, clarity, and effectiveness across the entire codebase. Here are key elements to consider when defining a documentation standard:

-

Documentation Types:

- Identify the different types of documentation needed for the project. This may include code comments, inline documentation, README files, user manuals, API documentation, architectural documents, testing documentation, and more.

-

Document Structure and Format:

- Define a consistent structure and format for each type of document. This includes the use of headings, sections, and subsections, as well as the formatting of text, code samples, and examples.

-

Naming Conventions:

- Establish naming conventions for documents, sections, and files. Consistent and intuitive naming makes it easier for team members to locate and reference the information they need.

-

Language and Tone:

- Specify the language and tone to be used in documentation. Determine whether a formal or informal style is more appropriate for the project and ensure consistency across all documents.

-

Versioning and History:

- Define how version information and history should be documented. This may include version numbers, release notes, and a changelog to track changes made over time.

-

Code Comments:

- Provide guidelines for writing code comments, including the preferred style, content, and placement within the code. Encourage developers to comment on complex or non-intuitive sections of the code.

-

Inline Documentation:

- Specify the format and conventions for inline documentation using tools such as Doxygen, Javadoc, or similar. This includes documenting functions, classes, methods, and variables.

-

Readability and Consistency:

- Emphasize the importance of readability and consistency throughout the documentation. Consistent terminology, formatting, and organization contribute to a more accessible and understandable documentation set.

-

Images and Diagrams:

- If the project involves architectural diagrams, flowcharts, or other visual elements, define standards for creating and incorporating images. Include guidelines for image formats, resolution, and placement.

-

Review and Approval Process:

- Establish a process for reviewing and approving documentation. This may involve peer reviews, technical reviews, or other mechanisms to ensure the accuracy and quality of the documentation.

-

Collaboration and Ownership:

- Clarify how collaboration on documentation should occur, especially in projects with multiple contributors. Assign ownership of different sections or types of documentation to specific team members to ensure accountability.

-

Tools and Platforms:

- Specify the tools and platforms that will be used for documentation. This may include version control systems, collaborative editing platforms, documentation generators, or specific file formats.

-

Documentation Maintenance:

- Outline procedures for keeping documentation up-to-date. Define responsibilities for maintaining and updating documentation, especially when changes are made to the codebase.

-

Training and Onboarding Documentation:

- If applicable, include guidelines for creating documentation that supports training and onboarding of new team members. This documentation should help new members understand the project quickly.

-

Accessibility Considerations:

- Consider accessibility guidelines to ensure that documentation is accessible to individuals with disabilities. This may involve using accessible formats, providing alternative text for images, and ensuring readability for screen readers.

-

Legal and Licensing Information:

- Include guidelines for documenting legal and licensing information, such as open-source licenses or proprietary restrictions.

-

Templates:

- Provide templates or examples for different types of documentation to streamline the creation process and maintain consistency.

Process Standard, Product Standard, Interchange Standard

In the context of software development and other engineering disciplines, standards are essential for ensuring consistency, interoperability, and quality. Three types of standards that play crucial roles in various aspects of the development process are Process Standards, Product Standards, and Interchange Standards.

-

Process Standards:

- Definition: Process standards define the methods, practices, and procedures to be followed during the software development life cycle. These standards aim to establish a consistent and effective process for creating software.

- Examples:

- Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) Standards: Guidelines for stages such as requirements analysis, design, coding, testing, and maintenance.

- Coding Standards: Rules and conventions for writing code, including naming conventions, formatting, and documentation practices.

- Testing Standards: Procedures for planning, executing, and documenting testing activities.

- Project Management Standards: Guidelines for project planning, scheduling, and tracking.

-

Product Standards:

- Definition: Product standards focus on the characteristics, features, and quality attributes of the software product itself. These standards define the expectations and criteria that the final product should meet to ensure its quality and reliability.

- Examples:

- Quality Assurance Standards: Criteria for ensuring the quality of the software, including reliability, performance, security, and maintainability.

- User Interface (UI) Standards: Guidelines for designing a consistent and user-friendly interface.

- Documentation Standards: Specifications for creating comprehensive and well-organized documentation.

- Compatibility Standards: Criteria for ensuring compatibility with specific platforms, browsers, or hardware.

-

Interchange Standards:

- Definition: Interchange standards focus on facilitating communication and interoperability between different software systems, tools, or components. These standards ensure that data and information can be exchanged seamlessly across diverse environments.

- Examples:

- Data Interchange Formats: Standards such as JSON, XML, or CSV that define how data is formatted for exchange between systems.

- API Standards: Specifications for creating Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) to enable communication between different software applications.

- File Format Standards: Specifications for standard file formats (e.g., PDF, CSV) to ensure compatibility across different applications.

- Communication Protocols: Standards such as HTTP, HTTPS, or MQTT that govern how data is transmitted over networks.

Benefits of the Good Documentation

Good documentation plays a crucial role in software development and other technical fields, providing numerous benefits that contribute to the success of a project and the overall efficiency of a development team. Here are some key benefits of good documentation:

-

Facilitates Understanding:

- Internal Teams: Clear and well-structured documentation helps developers understand the codebase, architecture, and design decisions. It serves as a reference for team members, facilitating collaboration and knowledge sharing.

- New Team Members: Documentation aids in onboarding new team members by providing them with insights into the project's structure, coding standards, and best practices.

-

Supports Maintenance and Updates:

- Good documentation assists in maintaining and updating software over time. Developers can refer to documentation to understand the existing features, identify areas that need modification, and implement changes without introducing errors.

-

Enhances Collaboration:

- Documentation promotes collaboration by ensuring that team members are on the same page regarding project requirements, coding conventions, and development practices. It reduces misunderstandings and fosters effective communication within the team.

-

Saves Time and Resources:

- Having comprehensive documentation saves time by reducing the need for developers to reverse-engineer code or seek information from colleagues. This efficiency translates to saved resources and faster development cycles.

-

Improves Code Quality:

- Documentation encourages developers to adhere to coding standards and best practices. It promotes cleaner and more maintainable code by providing guidelines for code structure, naming conventions, and design patterns.

-

Supports Troubleshooting and Debugging:

- During troubleshooting and debugging, documentation serves as a valuable resource. Clear documentation allows developers to trace the flow of the code, understand the logic, and identify potential sources of errors more efficiently.

-

Aids in Testing:

- Documentation helps testing teams understand the expected behavior of the software. Test cases, test plans, and testing procedures documented in advance ensure thorough and systematic testing, reducing the likelihood of overlooking critical scenarios.

-

Ensures Consistency:

- Documentation establishes consistency in coding styles, naming conventions, and project structures. This consistency is essential for collaboration, readability, and maintainability, especially in large and complex codebases.

-

Facilitates Scalability:

- As projects grow in size and complexity, good documentation becomes even more critical. It allows development teams to scale effectively by providing a foundation for understanding and managing increasingly intricate systems.

-

Enables Decision-Making:

- Documentation serves as a reference for decision-making during various stages of development. It provides insights into design choices, trade-offs, and rationale, aiding developers and stakeholders in making informed decisions.

-

Enhances User Training and Support:

- Well-documented user manuals and guides improve the end-user experience. Users can easily understand how to use the software, troubleshoot common issues, and take full advantage of the available features.

-

Supports Compliance and Auditing:

- Documentation is crucial for compliance with industry standards, legal requirements, and auditing processes. It provides evidence of adherence to coding standards, security practices, and other regulatory requirements.

Requirement of Documentation

Documentation is a critical aspect of the software development process, and it serves various purposes at different stages of a project. Here are some key requirements for documentation in the software development lifecycle:

-

Requirements Gathering:

- Purpose: Understand and capture the needs and expectations of stakeholders.

- Documentation Requirements:

- Requirement Specifications: Clearly document functional and non-functional requirements.

- Use Case Diagrams: Illustrate how users interact with the system.

- User Stories: Break down requirements into manageable user-focused narratives.

- Stakeholder Interviews: Record insights gathered from discussions with project stakeholders.

-

Design Phase:

- Purpose: Define the architecture, structure, and components of the software.

- Documentation Requirements:

- System Architecture: Describe the overall structure of the system.

- Design Specifications: Document the detailed design of modules and components.

- Data Models: Illustrate the structure of the data used by the system.

- Interface Design: Detail the design of user interfaces, APIs, and external interfaces.

-

Coding and Implementation:

- Purpose: Provide guidelines and references for developers to implement the design.

- Documentation Requirements:

- Coding Standards: Define coding conventions, styles, and best practices.

- API Documentation: Detail the interfaces and usage of APIs.

- Inline Comments: Add comments within the code to explain complex or critical sections.

-

Testing Phase:

- Purpose: Verify that the software meets specified requirements and is free of defects.

- Documentation Requirements:

- Test Plans: Outline the approach, resources, and schedule for testing.

- Test Cases: Detail specific test scenarios and expected outcomes.

- Test Reports: Summarize the results of testing, including any issues found.

-

Deployment and Operations:

- Purpose: Guide the deployment, configuration, and ongoing maintenance of the software.

- Documentation Requirements:

- Deployment Instructions: Provide step-by-step instructions for installing and configuring the software.

- Configuration Guides: Detail how to customize settings or configurations.

- Operations Manuals: Document procedures for routine maintenance, backups, and troubleshooting.

-

User Training and Support:

- Purpose: Assist users in understanding and effectively using the software.

- Documentation Requirements:

- User Manuals: Provide comprehensive guides for end-users.

- FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions): Address common user queries and concerns.

- Troubleshooting Guides: Assist users in resolving common issues.

-

Change Management:

- Purpose: Record and communicate changes made to the software.

- Documentation Requirements:

- Version Control Logs: Document changes made to the codebase over time.

- Change Logs: Summarize modifications, bug fixes, and enhancements for each release.

- Release Notes: Communicate changes and new features to end-users.

-

Project Management:

- Purpose: Facilitate effective project planning, tracking, and decision-making.

- Documentation Requirements:

- Project Plans: Outline project timelines, milestones, and resource allocation.

- Meeting Minutes: Document decisions, action items, and discussions from project meetings.

- Risk Registers: Identify, assess, and document potential risks and mitigation strategies.

-

Legal and Compliance:

- Purpose: Ensure adherence to legal and regulatory requirements.

- Documentation Requirements:

- Licensing Information: Specify the terms and conditions under which the software can be used.

- Compliance Documentation: Detail how the software complies with relevant industry standards and regulations.

-

Knowledge Transfer:

- Purpose: Enable knowledge transfer among team members and facilitate future development.

- Documentation Requirements:

- Architecture and Design Documents: Serve as references for understanding the system's structure.

- Codebase Documentation: Include inline comments, coding standards, and other information for developers.

- Lessons Learned: Document insights gained during the project for future reference.

Importance of Documentation

Documentation is of paramount importance in the software development process and various other domains. It serves multiple purposes and provides numerous benefits, contributing to the success and efficiency of a project. Here are some key reasons highlighting the importance of documentation:

-

Knowledge Transfer:

- Importance: Facilitates the transfer of knowledge among team members.

- Explanation: Well-documented code, architecture, and design allow team members to understand and work with existing systems. It is particularly valuable during onboarding of new team members.

-

Collaboration and Communication:

- Importance: Enhances collaboration and communication within the development team and with stakeholders.

- Explanation: Documentation serves as a common reference point for discussions, meetings, and decision-making. It helps ensure that all team members are on the same page regarding project requirements, design, and implementation details.

-

Maintainability and Scalability:

- Importance: Aids in maintaining and scaling software systems.

- Explanation: Comprehensive documentation assists developers in making modifications, updates, and enhancements to the codebase. It reduces the risk of introducing errors during maintenance activities.

-

Code Understanding and Debugging:

- Importance: Assists in understanding code logic and facilitates debugging.

- Explanation: Comments and inline documentation provide insights into the purpose and functionality of code segments. This is crucial during troubleshooting and debugging activities, helping developers identify and address issues more efficiently.

-

Risk Mitigation:

- Importance: Contributes to risk mitigation by providing a record of decisions and justifications.

- Explanation: Documentation captures the rationale behind design choices, assumptions, and trade-offs. In the event of changes or challenges, this documentation serves as a valuable reference for understanding the context and reasoning behind previous decisions.

-

Efficient Onboarding:

- Importance: Accelerates the onboarding process for new team members.

- Explanation: Well-documented systems provide new team members with the necessary context and information to quickly understand the project's architecture, coding standards, and development practices.

-

Quality Assurance and Testing:

- Importance: Supports effective quality assurance and testing.

- Explanation: Test plans, test cases, and testing documentation guide the testing process, ensuring thorough coverage of test scenarios and contributing to the overall quality of the software.

-

User Training and Support:

- Importance: Assists end-users in understanding and using the software effectively.

- Explanation: User manuals, FAQs, and other documentation resources help users navigate the software, troubleshoot common issues, and take full advantage of its features.

-

Compliance and Legal Requirements:

- Importance: Ensures compliance with legal and regulatory standards.

- Explanation: Documentation includes licensing information, compliance details, and adherence to industry standards, addressing legal and regulatory requirements.

-

Decision-Making:

- Importance: Provides information for informed decision-making.

- Explanation: Documentation serves as a basis for making design decisions, planning project timelines, and evaluating the impact of proposed changes. It helps stakeholders make informed choices throughout the development process.

-

Project Planning and Management:

- Importance: Supports effective project planning, tracking, and management.

- Explanation: Documentation, such as project plans, meeting minutes, and risk registers, provides a framework for organizing and managing the project. It aids in setting goals, allocating resources, and tracking progress.

-

Legacy System Understanding:

- Importance: Facilitates understanding and maintenance of legacy systems.

- Explanation: For systems with a long lifespan, documentation becomes crucial for maintaining and evolving the software, especially as original team members may change or leave the project.

-

Customer and Stakeholder Communication:

- Importance: Enhances communication with customers and stakeholders.

- Explanation: Documentation, including requirements specifications and project documentation, provides a basis for clear communication with clients, ensuring that their expectations are understood and met.

Types of Documentation

Documentation is a comprehensive and multi-faceted aspect of the software development process, encompassing various types of documents created for different purposes and audiences. Here are several types of documentation commonly used in software development:

-

Requirements Documentation:

- Purpose: Define and capture the needs, expectations, and specifications of the software.

- Examples:

- Business Requirements Document (BRD)

- Functional Requirements Document (FRD)

- Use Cases

- User Stories

-

Architecture/Design Documentation:

- Purpose: Define the system's architecture, structure, and components.

- Examples:

- System Architecture Document

- High-Level Design (HLD) Document

- Low-Level Design (LLD) Document

- Data Flow Diagrams (DFD)

- Entity-Relationship Diagrams (ERD)

-

Technical Documentation:

- Purpose: Provide detailed technical information for developers, testers, and maintainers.

- Examples:

- API Documentation

- Code Comments

- Coding Standards

- Database Schema Documentation

- Deployment Procedures

-

End-User Documentation:

- Purpose: Assist end-users in understanding and using the software effectively.

- Examples:

- User Manuals

- Quick Start Guides

- FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

- Tutorials

- Online Help Documentation

-

Marketing Documentation:

- Purpose: Communicate the value proposition of the software to potential users or customers.

- Examples:

- Product Brochures

- Product Flyers

- Feature Highlights

- Case Studies

- Demos and Presentations

-

Testing Documentation:

- Purpose: Guide the testing process and document test scenarios and results.

- Examples:

- Test Plans

- Test Cases

- Test Scripts

- Test Results

- Regression Testing Documentation

-

Project Management Documentation:

- Purpose: Facilitate project planning, tracking, and management.

- Examples:

- Project Plans

- Gantt Charts

- Risk Registers

- Meeting Minutes

- Status Reports

-

Change Management Documentation:

- Purpose: Record and communicate changes made to the software.

- Examples:

- Version Control Logs

- Change Logs

- Release Notes

- Patch Notes

-

Legal and Compliance Documentation:

- Purpose: Ensure compliance with legal and regulatory requirements.

- Examples:

- Licensing Information

- Compliance Statements

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policies

-

Knowledge Transfer Documentation:

- Purpose: Facilitate knowledge transfer among team members.

- Examples:

- Lessons Learned

- Best Practices

- Knowledge Base Articles

- Technical Documentation Wiki

-

Training Documentation:

- Purpose: Support training sessions for team members or end-users.

- Examples:

- Training Manuals

- Training Modules

- Workshop Materials

- Training Videos

-

Customer Support Documentation:

- Purpose: Assist customer support teams in addressing user queries and issues.

- Examples:

- Troubleshooting Guides

- Knowledge Base

- FAQs for Support Teams

- Customer Communication Templates

Program Specification

A program specification, often referred to as a software specification or software requirements specification (SRS), is a detailed document that outlines the functional and non-functional requirements of a software application. It serves as a blueprint for the development team, providing a clear and comprehensive description of what the software is expected to achieve. The program specification typically includes information about the system's features, functionality, performance, design constraints, and user interactions.

System Requirements:

The document begins with an overview of the system requirements, detailing the hardware, software, and network specifications necessary for the program to run effectively. This section helps ensure that the environment in which the software operates is well-defined.

Major Application:

This section highlights the primary application or purpose of the software. It describes the problem or need the software addresses and the key functionalities it delivers. Major applications provide context for the subsequent detailed requirements.

Here are key components commonly found in a program specification:

-

Introduction:

- Purpose: Provides an overview of the document and the software project.

- Content:

- Brief project description.

- Objectives and goals of the software.

-

Scope:

- Purpose: Defines the boundaries of the software project.

- Content:

- Inclusions and exclusions.

- Description of what the software is expected to achieve.

-

Functional Requirements:

- Purpose: Describes the specific features and functionalities of the software.

- Content:

- Use cases or user stories.

- Detailed functional specifications for each feature.

- Input and output requirements.

- System behavior under different scenarios.

-

Non-Functional Requirements:

- Purpose: Specifies criteria related to performance, security, reliability, and other quality attributes.

- Content:

- Performance requirements (response time, throughput).

- Security requirements (authentication, authorization).

- Reliability and availability requirements.

- Usability and user interface requirements.

-

System Architecture:

- Purpose: Describes the overall structure and organization of the software.

- Content:

- High-level architecture.

- Components and modules.

- Data flow diagrams.

- Interface descriptions.

-

Data Model:

- Purpose: Describes the structure and relationships of the data used by the system.

- Content:

- Entity-Relationship Diagrams (ERD).

- Data entities and attributes.

- Data storage and retrieval mechanisms.

-

Assumptions and Constraints:

- Purpose: Identifies any assumptions made during the specification process and constraints that may impact the development.

- Content:

- Conditions assumed to be true.

- Limitations or constraints on the software design and implementation.

-

Dependencies:

- Purpose: Identifies external dependencies that the software relies on.

- Content:

- External libraries or frameworks.

- Third-party services or APIs.

-

User Interfaces:

- Purpose: Describes the graphical or textual interfaces that users will interact with.

- Content:

- Mockups or wireframes.

- User interface design guidelines.

-

Testing Requirements:

- Purpose: Outlines the testing criteria and procedures for validating the software.

- Content:

- Test cases for each functional requirement.

- Acceptance criteria.

- Performance testing requirements.

-

Documentation Requirements:

- Purpose: Specifies the documentation that should be produced during and after development.

- Content:

- User manuals.

- Technical documentation.

- Training materials.

-

Change Control:

- Purpose: Defines the procedures for handling changes to the software specification.

- Content:

- Change request process.

- Version control and change history.

-

Sign-Off:

- Purpose: Indicates the formal approval of the program specification.

- Content:

- Signature lines for stakeholders to indicate their approval.

Uses of Specification:

The program specification serves various purposes throughout the software development lifecycle:

- Communication: Communicates the expectations and requirements between stakeholders, including developers, project managers, and clients.

- Guidance: Acts as a blueprint for developers, guiding them during the coding and implementation phases.

- Verification: Provides a basis for verifying that the developed software meets the specified requirements.

- Documentation: Serves as documentation for future reference, aiding maintenance, troubleshooting, and updates.

- Decision Support: Assists in making informed decisions during the development process.

Features of Program Specification:

- Clarity: Ensures clear and unambiguous language to convey requirements.

- Completeness: Covers all aspects of the software, leaving no room for ambiguity.

- Consistency: Maintains consistency in terminology, formatting, and content throughout the document.

- Traceability: Enables traceability between requirements and different phases of development.

- Modularity: Organizes requirements in a modular fashion, making it easy to locate specific information.

- Measurability: Includes measurable criteria for performance, security, and other quality attributes.

Classification of Specification Styles:

-

Natural Language Specification:

- Description: Uses human-readable language to articulate requirements.

- Advantages: Easily understood, accessible to non-technical stakeholders.

- Challenges: Prone to ambiguity and interpretation differences.

-

Structured Specification:

- Description: Organizes requirements in a structured format using tables, diagrams, or charts.

- Advantages: Enhances clarity, reduces ambiguity, and aids in visualization.

- Challenges: May be more formal and require training for interpretation.

-

Formal Specification:

- Description: Employs mathematical or logical notation to express requirements precisely.

- Advantages: Minimizes ambiguity, provides a basis for automated verification.

- Challenges: Requires specialized knowledge, potentially time-consuming.

-

Graphical Specification:

- Description: Represents requirements using graphical models like flowcharts, UML diagrams, or state charts.

- Advantages: Facilitates visualization, especially for system architecture and interactions.

- Challenges: May not capture all details, could be less detailed than text-based specifications.

-

Executable Specification:

- Description: Represents requirements in a form that can be directly executed or tested.

- Advantages: Enables automated testing, immediate feedback on requirements.

- Challenges: Requires additional effort in development, maintenance, and validation.

System flowchart

A system flowchart, also known as a system process diagram, is a visual representation of the flow of data within a system or process. It illustrates how information moves through various components, processes, and decision points in a system. System flowcharts are valuable tools for understanding, analyzing, and documenting complex processes, providing a high-level overview of the system's functionality.

Here are the key elements and conventions typically found in a system flowchart:

-

Terminal (Oval):

- Symbol: Oval shape.

- Purpose: Represents the start or end of a process.

- Usage: Used at the beginning and end of the flowchart.

-

Process (Rectangle):

- Symbol: Rectangular shape.

- Purpose: Represents a specific task, operation, or activity within the system.

- Usage: Used to describe actions or processes.

-

Decision (Diamond):

- Symbol: Diamond shape.

- Purpose: Represents a decision point where a condition is evaluated.

- Usage: Used for branching paths based on yes/no or true/false conditions.

-

Input/Output (Parallelogram):

- Symbol: Parallelogram shape.

- Purpose: Represents input from or output to external entities or sources.

- Usage: Used for data input or output operations.

-

Connector (Circle):

- Symbol: Circular shape.

- Purpose: Indicates a connection to another part of the flowchart on the same page or a different page.

- Usage: Used to avoid clutter and simplify the flowchart.

-

Arrow (Flow Line):

- Symbol: Arrow connecting different symbols.

- Purpose: Shows the direction of flow between symbols, indicating the sequence of actions.

- Usage: Used to connect symbols and illustrate the order of processes.

Data Flow Diagram

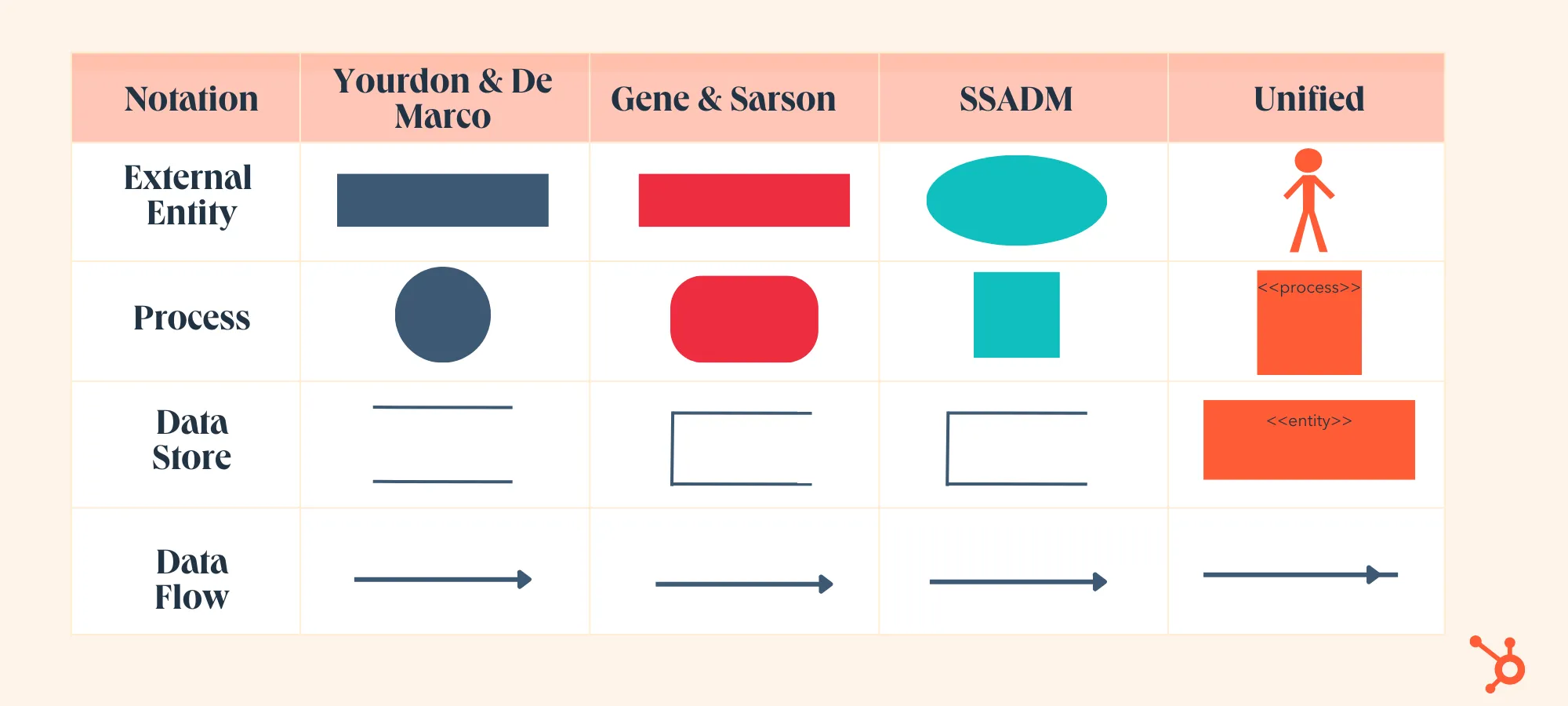

A Data Flow Diagram (DFD) is a visual representation that depicts the flow of data within a system or process. It is a powerful tool used in system analysis and design to illustrate how data moves between different components of a system. DFDs are particularly useful for understanding, analyzing, and documenting complex systems and processes.

Key components and conventions used in Data Flow Diagrams:

-

Processes:

- Symbol: Circle or oval.

- Description: Represents a specific function or process that transforms input data into output data.

- Usage: Used to show activities or operations performed within the system.

-

External Entities:

- Symbol: Rectangle.

- Description: Represents external entities such as users, systems, or organizations that interact with the system but are not part of it.

- Usage: Used to show data sources or destinations outside the system boundaries.

-

Data Flows:

- Symbol: Arrow.

- Description: Represents the flow of data between processes, external entities, and data stores.

- Usage: Used to illustrate the movement of data from one point to another in the system.

-

Data Stores:

- Symbol: Open rectangle.

- Description: Represents repositories where data is stored persistently.

- Usage: Used to show databases, files, or other storage locations.

-

Data Flow Diagram Levels:

- Context Level (Level 0): Provides an overview of the entire system, showing external entities and the main processes.

- Level 1: Breaks down the processes into more detailed subprocesses.

- Level 2 and Beyond: Further elaborates on the details of processes and data flows.

Basic Element of Data Flow Diagram

Data Flow Diagrams (DFDs) use several basic elements to visually represent the flow of data within a system. These elements help depict processes, data stores, data flows, and external entities. Here are the fundamental elements of a Data Flow Diagram:

-

Processes:

- Symbol: Circle or oval.

- Description: Represents a specific function or process that transforms input data into output data within the system.

- Usage: Used to illustrate activities or operations performed by the system.

-

External Entities:

- Symbol: Rectangle.

- Description: Represents external entities such as users, systems, or organizations that interact with the system but are not part of it.

- Usage: Used to show data sources or destinations outside the system boundaries.

-

Data Flows:

- Symbol: Arrow.

- Description: Represents the flow of data between processes, external entities, and data stores.

- Usage: Used to illustrate the movement of data from one point to another in the system.

-

Data Stores:

- Symbol: Open rectangle.

- Description: Represents repositories where data is stored persistently.

- Usage: Used to show databases, files, or other storage locations.

-

Data Flow Diagram Levels:

- Context Level (Level 0): Provides an overview of the entire system, showing external entities and the main processes.

- Level 1: Breaks down the processes into more detailed subprocesses.

- Level 2 and Beyond: Further elaborates on the details of processes and data flows.

-

Data Flow Diagram Annotations:

- Symbol: Text or labels.

- Description: Provides additional information or descriptions for processes, data flows, or other elements within the DFD.

- Usage: Used to add clarity and details to the diagram.

Now, let's briefly describe each of these basic elements in the context of a simple Data Flow Diagram:

Example Scenario:

- External Entity (User): Represents a user interacting with the system.

- Process (Order Processing): Represents a system process for processing customer orders.

- Data Flow (Order Information): Represents the flow of order information from the user to the order processing process.

- Data Store (Order Database): Represents a data store where order information is stored persistently.

- Annotation (Process Details): Provides additional information about the order processing process.

DFDs serve as powerful tools for system analysis and design, providing a clear and structured way to represent the flow and transformation of data within a system. They aid in communication among stakeholders, system understanding, and documentation.

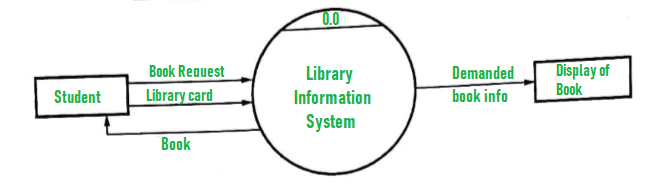

Example of Data Flow Diagram

DFD for Library Management System:

Data Flow Diagram (DFD) depicts the flow of information and the transformation applied when data moves in and out of a system. The overall system is represented and described using input, processing, and output in the DFD. The inputs can be:

- Book request when a student requests for a book.

- Library card when the student has to show or submit his/her identity as proof.

The overall processing unit will contain the following output that a system will produce or generate:

- The book will be the output as the book demanded by the students will be given to them.

- Information on the demanded book should be displayed by the library information system that can be used by the student while selecting the book which makes it easier for the student.

Context Level (Level 0) DFD:

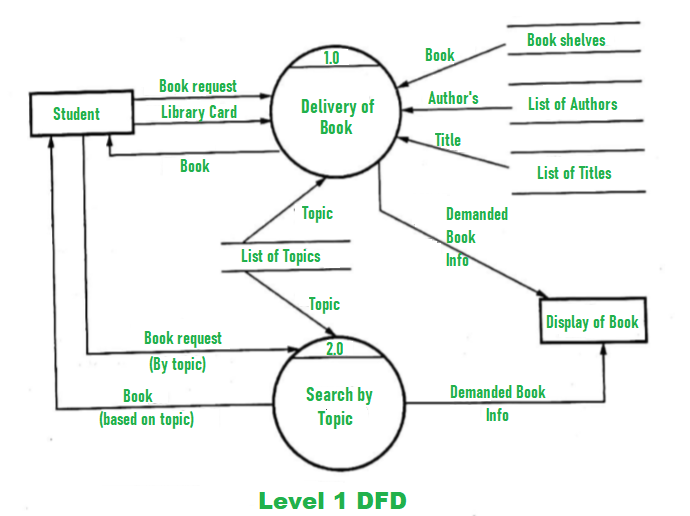

Level 1 DFD (Detailed Order Processing):

At this level, the system has to show or exposed with more details of processing. The processes that are important to be carried out are: Book delivery Search by topic List of authors, List of Titles, List of Topics, the bookshelves from which books can be located are some information that is required for these processes. Data store is used to represent this type of information.

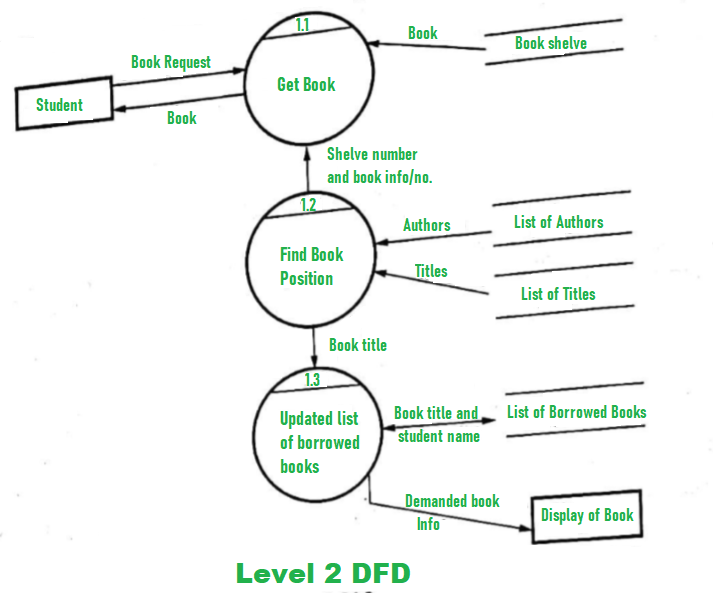

Level 2 DFD (Further Detail on Check Product Availability):

Out of scope:

Other activities like purchasing of new books, replacement of old books or charging a fine are not considered in the above system.

Leveling the Data Flow Diagram

In Data Flow Diagrams (DFDs), leveling refers to the process of decomposing a high-level diagram into lower-level diagrams to provide more detail and granularity. DFDs are hierarchical, and they can have multiple levels, with each level providing a more detailed view of the system. The levels are typically labeled as Level 0, Level 1, Level 2, and so on.